Henstock–Kurzweil integral

In mathematics, the Henstock–Kurzweil integral, also known as the Denjoy integral (pronounced [dɑ̃ˈʒwa]) and the Perron integral, is one of a number of definitions of the integral of a function. It is a generalization of the Riemann integral which in some situations is more useful than the Lebesgue integral.

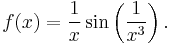

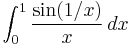

This integral was first defined by Arnaud Denjoy (1912). Denjoy was interested in a definition that would allow one to integrate functions like

This function has a singularity at 0, and is not Lebesgue integrable. However, it seems natural to calculate its integral except over [−ε,δ] and then let ε, δ → 0.

Trying to create a general theory Denjoy used transfinite induction over the possible types of singularities which made the definition quite complicated. Other definitions were given by Nikolai Luzin (using variations on the notions of absolute continuity), and by Oskar Perron, who was interested in continuous major and minor functions. It took a while to understand that the Perron and Denjoy integrals are actually identical.

Later, in 1957, the Czech mathematician Jaroslav Kurzweil discovered a new definition of this integral elegantly similar in nature to Riemann's original definition which he named the gauge integral; the theory was developed by Ralph Henstock. Due to these two important mathematicians, it is now commonly known as the Henstock–Kurzweil integral. The simplicity of Kurzweil's definition made some educators advocate that this integral should replace the Riemann integral in introductory calculus courses, but this idea has not gained traction.

Contents |

Definition

Henstock's definition is as follows:

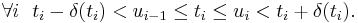

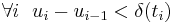

Given a tagged partition P of [a, b], say

and a positive function

which we call a gauge, we say P is  -fine if

-fine if

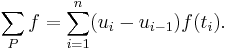

For a tagged partition P and a function

we define the Riemann sum to be

Given a function

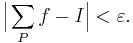

we now define a number I to be the Henstock–Kurzweil integral of f if for every ε > 0 there exists a gauge  such that whenever P is

such that whenever P is  -fine, we have

-fine, we have

If such an I exists, we say that f is Henstock–Kurzweil integrable on [a, b].

Cousin's theorem states that for every gauge  , such a

, such a  -fine partition P does exist, so this condition cannot be satisfied vacuously. The Riemann integral can be regarded as the special case where we only allow constant gauges.

-fine partition P does exist, so this condition cannot be satisfied vacuously. The Riemann integral can be regarded as the special case where we only allow constant gauges.

Properties

Let f: [a, b] → R be any function.

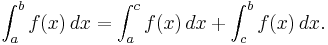

If a < c < b, then f is Henstock–Kurzweil integrable on [a, b] if and only if it is Henstock–Kurzweil integrable on both [a, c] and [c, b], and then

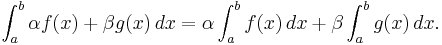

The Henstock–Kurzweil integral is linear, i.e., if f and g are integrable, and α, β are reals, then αf + βg is integrable and

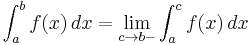

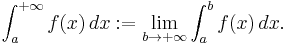

If f is Riemann or Lebesgue integrable, then it is also Henstock–Kurzweil integrable, and the values of the integrals are the same. The important Hake's theorem states that

whenever either side of the equation exists, and symmetrically for the lower integration bound. This means that if f is "improperly Henstock–Kurzweil integrable", then it is properly Henstock–Kurzweil integrable; in particular, improper Riemann or Lebesgue integrals such as

are also Henstock–Kurzweil integrals. This shows that there is no sense in studying an "improper Henstock–Kurzweil integral" with finite bounds. However, it makes sense to consider improper Henstock–Kurzweil integrals with infinite bounds such as

For many types of functions the Henstock–Kurzweil integral is no more general than Lebesgue integral. For example, if f is bounded, the following are equivalent:

- f is Henstock–Kurzweil integrable,

- f is Lebesgue integrable,

- f is Lebesgue measurable.

In general, every Henstock–Kurzweil integrable function is measurable, and f is Lebesgue integrable if and only if both f and |f| are Henstock–Kurzweil integrable. This means that the Henstock–Kurzweil integral can be thought of as a "non-absolutely convergent version of Lebesgue integral". It also implies that the Henstock–Kurzweil integral satisfies appropriate versions of the monotone convergence theorem (without requiring the functions to be nonnegative) and dominated convergence theorem (where the condition of dominance is loosened to g(x) ≤ fn(x) ≤ h(x) for some integrable g, h).

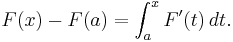

If F is differentiable everywhere (or with countable many exceptions), the derivative F′ is Henstock–Kurzweil integrable, and its indefinite Henstock–Kurzweil integral is F. (Note that F′ need not be Lebesgue integrable.) In other words, we obtain a simpler and more satisfactory version of the second fundamental theorem of calculus: each differentiable function is, up to a constant, the integral of its derivative:

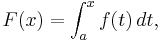

Conversely, the Lebesgue differentiation theorem continues to holds for the Henstock–Kurzweil integral: if f is Henstock–Kurzweil integrable on [a, b], and

then F′(x) = f(x) almost everywhere in [a, b] (in particular, F is almost everywhere differentiable).

The space of all Henstock–Kurzweil-integrable functions is often endowed with the Alexiewicz norm, with respect to which it is barrelled but incomplete.

McShane integral

Interestingly, Lebesgue integral on a line can also be presented in a similar fashion.

First of all, change of

to

(here  is a

is a  -neighbourhood of a) in the notion of

-neighbourhood of a) in the notion of  -fine partition yields a definition of the Henstock–Kurzweil integral equivalent to the one given above. But after this change we can drop condition

-fine partition yields a definition of the Henstock–Kurzweil integral equivalent to the one given above. But after this change we can drop condition

and get a definition of McShane integral, which is equivalent to the Lebesgue integral.

References

- Das, A.G. (2008). The Riemann, Lebesgue, and Generalized Riemann Integrals. Narosa Publishers. ISBN 978-8173199332.

- Swartz, Charles W.; Kurtz, Douglas S. (2004). Theories of Integration: The Integrals of Riemann, Lebesgue, Henstock-Kurzweil, and McShane. Series in Real Analysis. 9. World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 978-9812566119.

- Kurzweil, Jaroslav (2002). Integration Between the Lebesgue Integral and the Henstock-Kurzweil Integral: Its Relation to Locally Convex Vector Spaces. Series in Real Analysis. 8. World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 978-9812380463.

- Bartle, Robert G. (2001). A Modern Theory of Integration. Graduate Studies in Mathematics. 32. American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0821808450.

- Swartz, Charles W. (2001). Introduction to Gauge Integrals. World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 978-9810242398.

- Leader, Solomon (2001). The Kurzweil-Henstock Integral & Its Differentials. Pure and Applied Mathematics Series. CRC. ISBN 978-0824705350.

- Kurzweil, Jaroslav (2000). Henstock-Kurzweil Integration: Its Relation to Topological Vector Spaces. Series in Real Analysis. 7. World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 978-9810242077.

- Lee, Peng-Yee; Výborný, Rudolf (2000). Integral: An Easy Approach after Kurzweil and Henstock. Australian Mathematical Society Lecture Series. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521779685.

- Bartle, Robert G.; Sherbert, Donald R. (1999). Introduction to Real Analysis (3rd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0471321484.

- Gordon, Russell A. (1994). The integrals of Lebesgue, Denjoy, Perron, and Henstock. Graduate Studies in Mathematics. 4. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0821838051.

- Čelidze, V G; Džvaršeǐšvili, A G (1989). The Theory of the Denjoy Integral and Some Applications. Series in Real Analysis. 3. World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 978-9810200213.

- Lee, Peng-Yee (1989). Lanzhou Lectures on Henstock Integration. Series in Real Analysis. 2. World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 978-9971508913.

- Henstock, Ralph (1988). Lectures on the Theory of Integration. Series in Real Analysis. 1. World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 978-9971504502.

- McLeod, Robert M. (1980). The generalized Riemann integral. Carus Mathematical Monographs. 20. Washington, D.C.: Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0883850213.

External links

The following are additional resources on the web for learning more:

- http://www.math.vanderbilt.edu/~schectex/ccc/gauge/

- http://www.math.vanderbilt.edu/~schectex/ccc/gauge/letter/

|

|||||||||||

![a = u_0 < u_1 < \cdots < u_n = b, \ \ t_i \in [u_{i-1}, u_i]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d4077f14bd83b975dc8791de1eaf4cb4.png)

![\delta \colon [a, b] \to (0, \infty),\,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/fe88a6f29b9a4be4c53b6598e269e2d6.png)

![f \colon [a, b] \to \mathbb{R}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/83917025e687324e389eecda76d8f3ec.png)

![f \colon [a, b] \to \mathbb{R},](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/5311adfd3a95f3fe67fe6ce08e4bd7b9.png)

![\forall i \ \ [u_{i-1},u_i]\subset U_{\delta (t_i)}(t_i)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/571fa4c8ad531ac176f4fbc4f216da42.png)

![t_i \in [u_{i-1}, u_i]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/adbb67317b1722be34582cab742196c3.png)